This is the last week of summer and I am starting training at a new job while still working my old job and about to go away for my cousin's wedding, SO! before Jane gets lost in the shuffle I want to put out an unfinished post I had stewing around.

I've been thinking a lot about escapism since I started reading Austen. Deresiewicz writes about how non-escapist Austen was in her own writing. She didn't write Gothic romance, though she appreciated that genre: she wrote about women's lives as they were for ladies in small English countries. With her narrow focus, rooted in a context she knew intimately, she revealed universal human truths. People weren't running around Europe, getting locked up in ruined castles. They were talking with their neighbors, falling in love, and going to dances.

But even if her novels were anti-escapist for her time, they are escapes for me now. I don't have a grasp of where my place in the world is, and a world where men of a certain status had the choice of lawyer, clergy, soldier, or sailor seems kinda nice. Her life was so different from mine that I want to escape into her novels, and I don't think this is uncommon. This new movie Austenland seems to tap into that, though I haven't seen it; modern day women go to a Jane Austen theme park to dress up and hope to find their own happy ending. And her novels were escapes for men in the trenches during WWI.

Which would lead me to...

Rudyard Kipling...Science Fiction, romance, pulp/trash...criticism against escapism sort of lame, and I don't mean "escapist" in a negative way. I recognize my reality in Austen reality, but the customs are so different...What does it mean, this word "escapist"? A blogger on romance fiction says: "I’ve always pushed back against the idea that romance is escapist in a “special” way. But that’s probably because of the way I define the word. For me, romance is no more (or less) escapist than many other activities I engage in. We act as if we all know what we mean when we invoke the term, but I’m not sure we’re defining it the same way. I would define it, in this discussion, as a cognitive activity that takes my mind to a different place from its everyday life and provides different types of stimulation, comfort, and/or cognitive stretching. Using that definition, music is an escape (both listening and playing). My scholarly research can be an escape from the modern world."

Escaping into fiction: healthier than drugs or alcohol, but not as easy.

I never got around to finishing that post, once I realized what a loaded term "escapist" was.

Monday, August 26, 2013

Monday, August 19, 2013

Winding down...book discussions and Persuasion.

I appreciated this hot day, and I will enjoy the ones that are to follow, but I have to face reality: Summer is winding down, and with it, mah blurg. I've read eight full books, three essays, and a smattering of assorted Austen-related goodies, and written about a fraction of them.

Today was really special. I had a book discussion on Northanger Abbey with four intelligent, well-read friends. We shared tea, cheese and crackers, and cookies while talking over our favorite things about NA (the "case for innocence," the punctuation and "tastefully ornamental" sentences, and of course, her sharp irony) and differing opinions on Henry Tilney (by turns a "dreamy" educator who really helps improve Catherine's worldview and "a condescending man-splainer"--but nowhere near as bad as this guy). I felt really lucky to have friends who wanted to spend time talking about Austen. And another exciting thing that came from this: We will be meeting in a few months to discuss Mansfield Park! It was a lovely afternoon. I felt so happy before the discussion, after picking up flowers and walking home with a bag of cookies from a local bakery in my hand. I was happy that this was my life: Baked goods, fresh-cut flowers, and a book discussion.

So, to rewind: While on vacation I read Persuasion, which was the first Austen work I read, back with the brilliant Mr. Youngblood in my high-school English class (and apart from his intelligence and influence, he is a total silver fox). I wanted to read it last for that reason (not the silver fox reason), but also because it was her last novel, her oldest heroine, and her most "autumnal." It's important to be seasonal, as anyone who has seen the costumes in Far From Heaven can tell you.

It was difficult to find time to read on the vacation. I started the novel on the ride to St. John, but once there had trouble reading more than a page or two at a time. What with the views, the people, and the claims of the salt-water pools (where you could open your eyes underwater without it burning!), it was hard to read more than a paragraph without losing my place. And if I decided to really SIT DOWN AND READ, I did so in a hammock, where I promptly fell asleep. But boy, I tried! I took it everywhere--by the pool, on the boat, to various beaches. In a box, with a fox....One of my parents used it as a coaster when I wasn't looking. And it's not even my book, so keep that in mind if I ask to borrow a book.

Maybe it was the distractions, but I had a bit of trouble keeping track of people in this book. Coming off of E, especially, it seemed there were more families and groupings than usual. I found myself confusing the Crofts and the Harvilles--there were so many navy characters!

I liked that Anne Elliot, who was passive, calm, and reserved, was drawn to men who were warm and forthright. She was more suspicious of charm than the younger Austen heroines, who are initially drawn in by the Wickhams, Willoughbys, and Churchills. Anne observed of her cousin: "[He] was rational, discreet, polished--but he was not open. There was never any burst of feeling, any warmth of indignation or delight, at the evil or good of others. This, to Anne, was a decided imperfection. [...] She felt that she could so much more depend upon the sincerity of those who sometimes looked or said a careless or a hasty thing, than of those whose presence of mind never varied, whose tongue never slipped" (end of chap. 17). I like this sum-up of personality quite a bit, and find it interesting that Anne herself is such a composed, private person, unlike Louisa or Henrietta, the girls who you could view as warm and frank, but are seen as imprudent. I think that the above observation is something that holds true in almost all of Austen's novels--the men who are the most lovable are the ones who are the least polished, and they're often awkward.

Amy Smith, in her travelogue All Roads Lead to Austen, talks about how the men in Austen are never Prince Charming, rather, what makes them the hero is more a question of "fit;" a yin-yang match for the heroine. A partner who can balance and improve the other is the ideal. The Crofts provide an example of a happy couple: they do everything together, they are true partners. Mrs. Croft corrects the enthusiastic but sometimes careless driving of the Admiral, and he....I'm not quite sure what he does for her, but provide liveliness and good cheer. I love that scene, and the depiction of the Crofts. I like that characters are decidedly imperfect, but the romance comes from the idea that a union between people can bring them all closer to perfection.

Today was really special. I had a book discussion on Northanger Abbey with four intelligent, well-read friends. We shared tea, cheese and crackers, and cookies while talking over our favorite things about NA (the "case for innocence," the punctuation and "tastefully ornamental" sentences, and of course, her sharp irony) and differing opinions on Henry Tilney (by turns a "dreamy" educator who really helps improve Catherine's worldview and "a condescending man-splainer"--but nowhere near as bad as this guy). I felt really lucky to have friends who wanted to spend time talking about Austen. And another exciting thing that came from this: We will be meeting in a few months to discuss Mansfield Park! It was a lovely afternoon. I felt so happy before the discussion, after picking up flowers and walking home with a bag of cookies from a local bakery in my hand. I was happy that this was my life: Baked goods, fresh-cut flowers, and a book discussion.

So, to rewind: While on vacation I read Persuasion, which was the first Austen work I read, back with the brilliant Mr. Youngblood in my high-school English class (and apart from his intelligence and influence, he is a total silver fox). I wanted to read it last for that reason (not the silver fox reason), but also because it was her last novel, her oldest heroine, and her most "autumnal." It's important to be seasonal, as anyone who has seen the costumes in Far From Heaven can tell you.

Rocking the fall color palette.

Maybe it was the distractions, but I had a bit of trouble keeping track of people in this book. Coming off of E, especially, it seemed there were more families and groupings than usual. I found myself confusing the Crofts and the Harvilles--there were so many navy characters!

I liked that Anne Elliot, who was passive, calm, and reserved, was drawn to men who were warm and forthright. She was more suspicious of charm than the younger Austen heroines, who are initially drawn in by the Wickhams, Willoughbys, and Churchills. Anne observed of her cousin: "[He] was rational, discreet, polished--but he was not open. There was never any burst of feeling, any warmth of indignation or delight, at the evil or good of others. This, to Anne, was a decided imperfection. [...] She felt that she could so much more depend upon the sincerity of those who sometimes looked or said a careless or a hasty thing, than of those whose presence of mind never varied, whose tongue never slipped" (end of chap. 17). I like this sum-up of personality quite a bit, and find it interesting that Anne herself is such a composed, private person, unlike Louisa or Henrietta, the girls who you could view as warm and frank, but are seen as imprudent. I think that the above observation is something that holds true in almost all of Austen's novels--the men who are the most lovable are the ones who are the least polished, and they're often awkward.

Amy Smith, in her travelogue All Roads Lead to Austen, talks about how the men in Austen are never Prince Charming, rather, what makes them the hero is more a question of "fit;" a yin-yang match for the heroine. A partner who can balance and improve the other is the ideal. The Crofts provide an example of a happy couple: they do everything together, they are true partners. Mrs. Croft corrects the enthusiastic but sometimes careless driving of the Admiral, and he....I'm not quite sure what he does for her, but provide liveliness and good cheer. I love that scene, and the depiction of the Crofts. I like that characters are decidedly imperfect, but the romance comes from the idea that a union between people can bring them all closer to perfection.

Labels:

All Roads Lead to Austen,

Amy Elizabeth Smith,

autumn,

charm,

distractions,

Emma,

happy endings,

Jane Austen,

love,

Mansfield Park,

Northanger Abbey,

re-reading,

reading,

sense of an ending,

silver fox,

travel

Wednesday, July 24, 2013

Austen on Illness

Since finishing Sense and Sensibility a few month ago, I have been interested in the use of illness in Austen's work. Some of her most ridiculous characters suffer from or fear illness (often imaginary), and use it to control situations (like Mrs. Bennet and her "nerves"; the hypochondriac Mr. Woodhouse; and the tyrannical Mrs. Churchill, whose illnesses "never occurred but for her own convenience"). On the other hand, bright, lively, and "too" romantic characters suffer life-threatening illnesses and emerge transformed (Marianne Dashwood and Tom Bertram; Col. Brandon's first love is a notable exemption from the "re-emerged"). Illness is often used as a sort of punishment for high living, unhealthy ideas about romance, or betraying social values. Sound familiar? It's like how every prostitute from Manon Lescaut to Marguerite Gautier dies from tuberculous (usually). Illness is still today linked with punishment, unfortunately. Just look at what people continue to say about AIDS. And if you went to that link and feel a little sick, here is a tonic: Blanche tells Rose "AIDS is not a bad person's disease." I'm still surprised and a little sad that line doesn't receive a standing ovation. Austen uses this familiar message of illness and punishment, but allows her characters to face death and repent, albeit their lives proceed more subdued and responsible than before.

In her essay "On Being Ill," Virginia Woolf writes about the transformative aspect of illness. It reveals undiscovered places within ourselves; precipices and flowering valleys, that sort of thing. Illness can change our relation to the world. Through a feverish lens, "friends have changed, some putting on a strange beauty, others deformed to the squatness of toads, while the whole landscape of life lies remote and fair, like the shore seen from a ship far out at sea." It is akin to a religious experience; we see, for the first time, things that have always been there, such as the clouds moving and changing shape, and we speak the truth of our body. "Illness is the great confessional."

In S&S, after her life-threatening illness, Marianne tells her sister that it gave her time to reflect: "It has given me leisure and calmness for serious recollection," and the result is her resolution to "atone" to God and her family, and to live less selfishly. She sees her illness as her fault: "brought on by myself," but her survival was a rebirth, and a chance for change. Contrast this with Col. Brandon's first love, the doomed Eliza, who was "seduced" into "a life of sin" and consequently "faded" and became "worn down by acute suffering of every kind," finally dying, of course, of "consumption." Her sins were greater than Marianne's, and her tragic life serves as a warning against the allure of sensual libertines. But it isn't a clear-cut anecdote. Eliza's story is as much a tragedy about awful marriages, where an unkind husband whose "pleasures were not what they ought to have been" can send a young and inexperienced woman with a lively mind into the arms of another man. And then another and another. And yet part of me smirks at the story-within-a-story. It is so over the top, not to mention cliched, that it seems like a joke. Coupled with Brandon's tiresome and maudlin delivery, I have to wonder if it is inserted as a sort of reminder of the tragic Romances that would have been popular with girls like Marianne; this is the sort of pulp they eat up, but also, this sensibility destroys lives.

In MP, Tom Bertram's illness also provides a renewal: "He was the better for ever for his illness. He had suffered, and he had learnt to think, two advantages that he had never known before." He became "useful," "steady and quiet," and learned to "not [live] merely for himself." But first it was necessary to suffer, which Austen views as an advantage. True suffering humbles the extravagant, and the ones who can and will repent, do.

Tom and Marianne made the most out of their time away from the world, whereas others, like Mrs. Bennet, Mr. Woodhouse, and Mrs. Churchill, fake illness as an escape. Woolf writes about the opportunity for escape in illness, saying: "We cease to be soldiers in the army of the upright." The ill are deserters, and escape the daily drudge. That release from responsibility can be appealing to those who are unhappy or just childish and selfish. It is also a way for those with little or no power to exert their influence.

This use of illness as a punishment is uncomfortable with me, after all the garbage I've heard about STDs through the past decade, but it is worth looking at as a plot device. In Austen's world, every action has a consequence, and yet I don't believe illness is used merely as a punishment. The emphasis is on the somewhat spiritual suffering the characters undergo to develop and grow. Fevers are a good way to externalize that suffering. If I were a historian or new more about 19th century literature, I'm sure I could write a more nuanced perspective on this topic. It might be a fun dissertation.

In her essay "On Being Ill," Virginia Woolf writes about the transformative aspect of illness. It reveals undiscovered places within ourselves; precipices and flowering valleys, that sort of thing. Illness can change our relation to the world. Through a feverish lens, "friends have changed, some putting on a strange beauty, others deformed to the squatness of toads, while the whole landscape of life lies remote and fair, like the shore seen from a ship far out at sea." It is akin to a religious experience; we see, for the first time, things that have always been there, such as the clouds moving and changing shape, and we speak the truth of our body. "Illness is the great confessional."

In S&S, after her life-threatening illness, Marianne tells her sister that it gave her time to reflect: "It has given me leisure and calmness for serious recollection," and the result is her resolution to "atone" to God and her family, and to live less selfishly. She sees her illness as her fault: "brought on by myself," but her survival was a rebirth, and a chance for change. Contrast this with Col. Brandon's first love, the doomed Eliza, who was "seduced" into "a life of sin" and consequently "faded" and became "worn down by acute suffering of every kind," finally dying, of course, of "consumption." Her sins were greater than Marianne's, and her tragic life serves as a warning against the allure of sensual libertines. But it isn't a clear-cut anecdote. Eliza's story is as much a tragedy about awful marriages, where an unkind husband whose "pleasures were not what they ought to have been" can send a young and inexperienced woman with a lively mind into the arms of another man. And then another and another. And yet part of me smirks at the story-within-a-story. It is so over the top, not to mention cliched, that it seems like a joke. Coupled with Brandon's tiresome and maudlin delivery, I have to wonder if it is inserted as a sort of reminder of the tragic Romances that would have been popular with girls like Marianne; this is the sort of pulp they eat up, but also, this sensibility destroys lives.

In MP, Tom Bertram's illness also provides a renewal: "He was the better for ever for his illness. He had suffered, and he had learnt to think, two advantages that he had never known before." He became "useful," "steady and quiet," and learned to "not [live] merely for himself." But first it was necessary to suffer, which Austen views as an advantage. True suffering humbles the extravagant, and the ones who can and will repent, do.

Tom and Marianne made the most out of their time away from the world, whereas others, like Mrs. Bennet, Mr. Woodhouse, and Mrs. Churchill, fake illness as an escape. Woolf writes about the opportunity for escape in illness, saying: "We cease to be soldiers in the army of the upright." The ill are deserters, and escape the daily drudge. That release from responsibility can be appealing to those who are unhappy or just childish and selfish. It is also a way for those with little or no power to exert their influence.

This use of illness as a punishment is uncomfortable with me, after all the garbage I've heard about STDs through the past decade, but it is worth looking at as a plot device. In Austen's world, every action has a consequence, and yet I don't believe illness is used merely as a punishment. The emphasis is on the somewhat spiritual suffering the characters undergo to develop and grow. Fevers are a good way to externalize that suffering. If I were a historian or new more about 19th century literature, I'm sure I could write a more nuanced perspective on this topic. It might be a fun dissertation.

Saturday, July 20, 2013

Emma's Gay Best Friend

Frank Churchill is such a stereotypical gay best friend. Fashionable, charming, and witty, he shares in Emma's jokes and suspicions, and even criticizes people's hairstyles with her. They have an easy intimacy, with no romantic interest coming from his side. Really, it is sort of brilliant that his Clueless incarnation is this guy reading William Burroughs:

"Dyed in the wool homosexual."

"Dyed in the wool homosexual."

Thursday, July 18, 2013

Northanger Abbey

Northanger Abbey is a book that means a lot to me. I read it one intense winter, and it was so full of associations even then.

Returning to it with more Austen under my belt changed my reading a little. I was more critical, and the humor this time seemed maybe too distancing. I still really enjoyed it, but some of my pleasure was wrapped up in personal memories and the tactile pleasure of the worn and beautiful 1948 edition I have.

The book, with its cloth-covered binding and thick pages, takes me back five years.

This lady lived in Norwich! And then she brought me to Chicago, in a way.

I was twenty years old and studying in Norwich, England when I first learned about Northanger Abbey. I had heard the title but only had a vague idea what it was about. I mixed it up with my vague knowledge of Wuthering Heights. I was taking a course on Gothic Literature and we were reading The Mysteries of Udolpho, which is the novel that the heroine of NA reads. Our professor told us about Austen's satire on the Gothic Romance, and for awhile that's all I knew. I kept it in mind.

I traveled to London a number of times during the year. On one of my visits to the Tate Museum of Modern Art (which I never did get around to enjoying; it was always too crowded), I met Arthur. He was a volunteer, and an American. I asked him where to check my coat and he asked me to dinner. We went to a restaurant in Sofo, with pounding music and hot waiters. He ordered Veuve Clicquot and invited me to Cape Town for Christmas. I was lonely, and he seemed to be the man of my dreams. He complimented me and treated me with respect. He traveled a lot and had an apartment on the Thames. He was charming, and if you've read any Austen you'll know this should set off alarm bells. Austen wasn't a ready reference for me yet, though I did recognize his charm as "oozey." But it was so exciting.

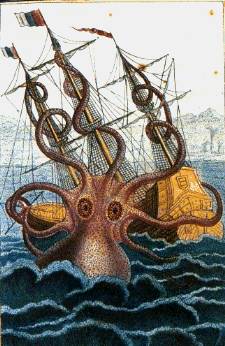

I was as much (if not more) infatuated with his apartment as I was with him. It was beautiful; full of modern furniture, hidden cabinets, and silver buttons. And South Africa became a reality when he bought my ticket. How exotic! I felt like Sally Bowles. I felt like my dreams were coming true. Part of me knew I couldn't be fully happy with an older man I wasn't sexually attracted to (and who bought cheap toilet paper), but I didn't put words to those thoughts, and so they weren't real. It was only later that I would describe him as a "kraken" in angry poetry scribbled in my journal.

I felt like the ship when I slept with him.

Things quickly became tense, and even though I told him I thought I shouldn't go along on his vacation, he told me he really didn't want to go alone. So I flew in cramped coach, grumbling that parents who bring babies on transcontinental flights should be ejected over water, while Arthur reclined in first class. On arrival we barely spoke, except for him to complain about a flight attendant being slow to bring his orange juice or something. I couldn't think of anything polite to say back. He had lost his veneer of charm, and had become crass, insulting, and thoughtless. The first day at the gay resort I spent like Catherine Moreland, unknown and unknowing. I sat by the pool, reading Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (which is funny, since I was reading Joyce when I switched to Austen this summer).

And along came the co-owner of the resort, to ask how everything was. He was young, handsome, and fun. But mostly he was just interested and active. He wanted to take me to a South African market; he wanted to show me penguins. Arthur, still mad about the orange juice, wanted to nap, so he let me go.

We had lunch overlooking the water and the walls were lined with old books, one of which was Northanger Abbey. I mentioned my interest, and maybe I talked about Gothic lit for awhile. I don't remember. I just remember being happy. We laughed a lot.

The next few days got sordid fast, and though I did nothing other than accepting attention, "trifles light as air are to the jealous confirmations strong as holy writ," and I ended up trading hands in what amounted to a financial transaction between the men. It's not a time I like to think of very much; it makes me sick and sad. But after Arthur left the resort, when Phil and I drove along the coast and up Table Mountain listening to Beyonce's "Smash Into You" I felt lifted up. It was exhilarating. It was the most passionate I had ever felt, and very different from the depressing affairs I had left behind in Cleveland. I had gone from numb and drunk, to in love, to broken, to exhilarated, and finally, disappointed.

Now when I re-read NA, in that edition Phil gave me from the restaurant with his tender inscription, the story of the ordinary, innocent heroine and her mixture of worldly, scheming friends and her educator/lover, as well as her very active imagination and her passivity, reminds me of that Christmas I spent in Cape Town.

Northanger Abbey describes places I walked in Bath so often, like the Crescent, Milsom and Cheap Street. It reminds me so much of England, much like when I re-read After Leaving Mr. MacKenzie and am right back in my room overlooking UEA's pond, drinking Tanqueray. But NA is tied not only with England, but Cape Town, Phil, and my family. There isn't another novel that is so evocative. It connects my personal life with my academic life--both Shakespeare and Gothic, and yet it was read only for pleasure. Of all the Austen novels, NA is the most significant to me. I identified with the exceedingly normal and naive Catherine, but unfortunately, I lacked her basic good sense and strong morals. I was drawn into the "Thorpe"-like web, too attracted to money and adventure. I know I didn't finish the novel while I was in Cape Town, because I feel like the condemnation of Isabella's character may have stung quite a bit.

Though this was more personal and difficult than anything I've shared on this blog, I don't think I would be doing myself justice if I didn't include this part of my relationship with Austen. It may not be perfectly told, but here it is.

Tuesday, July 16, 2013

Guest Post!

I asked Kathy Jo Gutgsell (aka "Mom") for her reflections on Pride and Prejudice, and she was generous enough to share her response. I hadn't really noticed the focal point Elizabeth played in her parents' marriage until Mom pointed it out. Here is what KJ had to say about her first time reading P&P:

"The first few chapters seemed like a soap opera and I wondered why I should care if these daughters found a husband? Whatever does Michael see in this? But then, before I knew it, I did care. I got caught up in the personalities of the sisters and the parents and the neighbors. I laughed out loud. I couldn't wait to know how it all turned out. I got hooked. Along the way, though, I couldn't help but notice the relationship between Elizabeth's mother and father. I've been married for decades, as you know, and I have some ideas about what makes a successful marriage. And their marriage came up short. What struck me was the pivotal point Elizabeth played. She was her dad's favorite and her mom's least favorite child. Elizabeth seemed to represent the gulf that existed in their marriage. We didn't get to see them talk out their differences. We saw their impatience with each other and then Mr. Bennet retreated to his study. But then, what went on behind closed doors we will never know."

That sense of being "caught up" in the characters is something I hear again and again about Austen. I'm glad my Mom got to see what I love about this talented author.

Thanks, Mom!

Sunday, July 14, 2013

A few things from other people

My sister sent this video from the Daily Show to me, telling me to note the title. Austen's P&P is ubiquitous!

And Betsy let me know about a first edition of P&P is on display in Scotland to celebrate the influence Austen has had over the two hundred years since the novel was published. Amazing! I'd love to see it. It would be like my twenty-first birthday, where I saw Austen's writing desk in the British library and Woolf's first version of Mrs. Dalloway. I cried.

I'd love to know if you all come across any Austen "sightings"! Thanks, Jessie and Betsy!

And Betsy let me know about a first edition of P&P is on display in Scotland to celebrate the influence Austen has had over the two hundred years since the novel was published. Amazing! I'd love to see it. It would be like my twenty-first birthday, where I saw Austen's writing desk in the British library and Woolf's first version of Mrs. Dalloway. I cried.

I'd love to know if you all come across any Austen "sightings"! Thanks, Jessie and Betsy!

Emma

I'm reading what is considered by some as Austen's masterpiece, with its heroine that Austen said no one but herself would like very much. It's a Dover Thrift Edition that was free from the Jane Austen Society of Louisiana--thank you! I'm enjoying it more than I did the first time around. It's funnier than I remember, with such gems as: "What is passable in youth is detestable in later age," said by the self-assured Emma to her friend Harriet. I agree with her there. Just looking out the window from a store in Boystown I see plenty of Peter Pan Gays.

And I really like Austen's joke about female writing, said again by Emma: "[the writing] is not the style of a woman; no, certainly, it is too strong and concise; not diffuse enough for a woman," which is what people said of Austen's novels before they knew she was a woman. Clueless, indeed.

But it's taking me a lot longer to read than with her other novels. I'm not sure why. I read bits at work, but it's hard to pay attention and there are other things I have to do, but also I'm not making time. I spend my free time sleeping, lunching, and watching Orange is the New Black. But enough with excuses! Gonna do better this week.

And I really like Austen's joke about female writing, said again by Emma: "[the writing] is not the style of a woman; no, certainly, it is too strong and concise; not diffuse enough for a woman," which is what people said of Austen's novels before they knew she was a woman. Clueless, indeed.

But it's taking me a lot longer to read than with her other novels. I'm not sure why. I read bits at work, but it's hard to pay attention and there are other things I have to do, but also I'm not making time. I spend my free time sleeping, lunching, and watching Orange is the New Black. But enough with excuses! Gonna do better this week.

Austenland

Elise and I saw the poster for the new movie Austenland when we went to see Noah Baumbach's Frances Ha. The poster looked totally corny, but we decided to watch the trailer. I was prepared to think the best part of the experience would be the deodorant commercial beforehand, but as soon as Jennifer Coolidge appeared on the the screen we were like: "Ooo! Let's see it." Glad that there's a pop Austen movie this summer. Good timing.

Check out the trailer below. What do you think?

Check out the trailer below. What do you think?

(And as a non-Austen sidenote: France Ha was wonderful. Go see it!)

Thursday, July 4, 2013

The lost sex scenes of Jane Austen

It's been awhile since I posted anything substantial, but I am working on a few things, they just aren't "there yet." I had a lot of time to read on our family vacation, and I've finished both Sense and Sensibility and Northanger Abbey. Right now I'm reading Amy Elizabeth Smith's All Roads Lead to Austen: a memoir about her travels in South America, hosting Austen book groups and looking for the "Austens" of Latin America. Sort of despite myself I've gotten sucked in and I am really enjoying it. More on that later.

I really wanted to post about my enthusiasm for Pride and Promiscuity, which Smith mentioned a few pages back. The lost sex scenes of Jane Austen? That sounds hilarious. I want! And as if just THAT weren't enough, I read this stuffy review by "Jennie," whose blog is called "The Bennett Sisters," that made me want it more:

"What is an amusing tribute to Jane Austen’s work in a fresh, quirky way, quickly becomes a one-part-pornography-one-part-erotic-fiction disaster that leaves you feeling a little nauseous. Indeed, I put the challenge to anyone to read it without blushing. "

Without blushing? My god, who is this woman? I think the joke sailed her right by, bye bye. But then she comes out with things like "the language is just one step too far down trash-lane" and "The author's husband is an ex-gigolo," (like that has anything to do with it). I detect a hint of slut-shaming disapproval, do you? The reviewer also identifies the most with Emma of all Austen characters. I'm just going to leave it there.

Here is a much more favorable review by Elsa Solender, and with considerable more insight.

Has anyone read or seen this collection? What do you think? I can't wait to get my hands on a copy.

I really wanted to post about my enthusiasm for Pride and Promiscuity, which Smith mentioned a few pages back. The lost sex scenes of Jane Austen? That sounds hilarious. I want! And as if just THAT weren't enough, I read this stuffy review by "Jennie," whose blog is called "The Bennett Sisters," that made me want it more:

"What is an amusing tribute to Jane Austen’s work in a fresh, quirky way, quickly becomes a one-part-pornography-one-part-erotic-fiction disaster that leaves you feeling a little nauseous. Indeed, I put the challenge to anyone to read it without blushing. "

Without blushing? My god, who is this woman? I think the joke sailed her right by, bye bye. But then she comes out with things like "the language is just one step too far down trash-lane" and "The author's husband is an ex-gigolo," (like that has anything to do with it). I detect a hint of slut-shaming disapproval, do you? The reviewer also identifies the most with Emma of all Austen characters. I'm just going to leave it there.

Here is a much more favorable review by Elsa Solender, and with considerable more insight.

Has anyone read or seen this collection? What do you think? I can't wait to get my hands on a copy.

Saturday, June 15, 2013

1. People can change

Ok, so I went into Mansfield Park knowing nothing. I was surprised by the differences in heroine (poor; physically weak; shy) and the severity of her surrounding friends and relations (cruel, or at the least negligent; crude; condescending; and cynical towards tradition and religion). Coming off of P&P, where the initially unlikeable character turns out to be one of the best people around, I pretty much expected that the immoral characters would redeem themselves. I didn't necessarily want this to happen, but I expected it to.

But I was surprised that the characters who were charming and morally bankrupt stayed that way, and subsequently lived out the consequences of their choices. The Crawfords surprised and fascinated me, as they are meant to. When I read Deresiewicz's chapter on MP, I was happy to see him link Mary C with Elizabeth Bennet, because I struggled with their similarities. Early on in MP, I thought that but for a slight difference, Mary Crawford could be the heroine of the novel. She was lively, charming, and clever--like Elizabeth Bennet. It's difficult not to like her. She's much more fun than Fanny. But she lacked Elizabeth's sincerity. Like I wrote a few weeks ago; Elizabeth said she hoped never to laugh at what was wise and good. Mary Crawford, on the other hand, does just that, mocking the Navy, the church, and her male relations, which was risque.

Maybe she didn't have a serious problem with the church or the taboo against premarital sex; but her instinct is to mock. Edmund sort of defends her by saying her mind isn't evil, but her words are. Mary doesn't examine her actions, but relies on what fashionable society has taught her to think. This inability to use her sharp intellect to examine her own mind is what stunts her love life, and therefore her destiny. When I heard one of my favorite satirical songs about wealth, fame, and society's flashy ideas of success the other day, it reminded me of Mary Crawford:

"I don't know what's right and what's real anymore. I don't know how I'm meant to feel anymore."

In The Madwoman in the Attic, Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar argue that Mary is an example of a woman trying to use her creativity to live life on her terms, and is punished by the patriarchy for her attempt. I don't have my own grasp on their take on Austen, though I'm sure it is very intelligent and well-thought out. Some of their interpretations of Austen's heroines are troubling to me, but I need to think more about it. But right off the bat, I don't agree that Mary's flaw is her inability to be passive; I think it's her insincerity.

And that about MP really surprised me: when the Crawfords appeared to be changing for the better, it turned out they were only faking it. They were playing a part, and Austen had been showing us throughout the entire novel how adept they were at acting and seducing. Really, we had no reason to expect anything better from them, except for our own hopefulness and the way we've been indoctrinated that characters can undergo a miraculous transformation from rakes to upright citizens.

And Fanny saw this, and stuck to her guns. She could call a spade a spade, and even when I expected her to accept the Crawford Charm in the end, she never did. She held out for her ideal and was rewarded in the end. She didn't give into the pressure from the patriarchy or even the awareness of her own unstable situation. That's pretty strong.

MP was harsher than I expected, and I appreciated it more for that.

But I was surprised that the characters who were charming and morally bankrupt stayed that way, and subsequently lived out the consequences of their choices. The Crawfords surprised and fascinated me, as they are meant to. When I read Deresiewicz's chapter on MP, I was happy to see him link Mary C with Elizabeth Bennet, because I struggled with their similarities. Early on in MP, I thought that but for a slight difference, Mary Crawford could be the heroine of the novel. She was lively, charming, and clever--like Elizabeth Bennet. It's difficult not to like her. She's much more fun than Fanny. But she lacked Elizabeth's sincerity. Like I wrote a few weeks ago; Elizabeth said she hoped never to laugh at what was wise and good. Mary Crawford, on the other hand, does just that, mocking the Navy, the church, and her male relations, which was risque.

Maybe she didn't have a serious problem with the church or the taboo against premarital sex; but her instinct is to mock. Edmund sort of defends her by saying her mind isn't evil, but her words are. Mary doesn't examine her actions, but relies on what fashionable society has taught her to think. This inability to use her sharp intellect to examine her own mind is what stunts her love life, and therefore her destiny. When I heard one of my favorite satirical songs about wealth, fame, and society's flashy ideas of success the other day, it reminded me of Mary Crawford:

"I don't know what's right and what's real anymore. I don't know how I'm meant to feel anymore."

In The Madwoman in the Attic, Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar argue that Mary is an example of a woman trying to use her creativity to live life on her terms, and is punished by the patriarchy for her attempt. I don't have my own grasp on their take on Austen, though I'm sure it is very intelligent and well-thought out. Some of their interpretations of Austen's heroines are troubling to me, but I need to think more about it. But right off the bat, I don't agree that Mary's flaw is her inability to be passive; I think it's her insincerity.

And that about MP really surprised me: when the Crawfords appeared to be changing for the better, it turned out they were only faking it. They were playing a part, and Austen had been showing us throughout the entire novel how adept they were at acting and seducing. Really, we had no reason to expect anything better from them, except for our own hopefulness and the way we've been indoctrinated that characters can undergo a miraculous transformation from rakes to upright citizens.

And Fanny saw this, and stuck to her guns. She could call a spade a spade, and even when I expected her to accept the Crawford Charm in the end, she never did. She held out for her ideal and was rewarded in the end. She didn't give into the pressure from the patriarchy or even the awareness of her own unstable situation. That's pretty strong.

MP was harsher than I expected, and I appreciated it more for that.

Tuesday, June 11, 2013

the end of Mansfield Park

After another day of dusting and re-organizing dildos at the Toy Gallery, I came home with a six pack of PBR and the desire only to pee and then sit outside and read. I didn't move until I had finished MP. Up until the last chapter I expected things to turn around. I don't want to spoil the book for anyone, so I won't go into details. But let me just say: I was surprised. I think I may eventually have to go into some "spoilers" because there are a lot of expectations that Austen overturned for me in this novel. Well, really, three. But three big ones:

1. People can change and improve

2. Even unlikeable characters will end up happy and loved

3. Men/wealthier/more worldly people generally know what's better for women/the less fortunate/innocent people

I should clarify, that though I may not agree with the above statements, I sort of expected that they would hold true in MP. That's what I mean when I say my expectations were overturned.

1. People can change and improve

2. Even unlikeable characters will end up happy and loved

3. Men/wealthier/more worldly people generally know what's better for women/the less fortunate/innocent people

I should clarify, that though I may not agree with the above statements, I sort of expected that they would hold true in MP. That's what I mean when I say my expectations were overturned.

Mansfield Park for the first time

MP is the last Austen novel I will read for the first time.* My memories of Persuasion and S&S are pretty foggy--I read them eons ago, back when I was a dewy-eyed child (slash in high school)--but I know the major parts will come back as I read them. In a way they will be new to me, because I have changed: I am a different reader than I was in high school. Still, I won't be experiencing them for the first time. As much as I enjoy the pleasures of rereading, I am conscious while reading MP that I will never meet and get to know these characters in this way again.

As inevitable as MP may seem to someone who knows Austen's novels inside and out, for me it is still excitingly new and unexpected. Like--Fanny visits her family?! I read Vol. III, chapters 7 to 12 last night and I couldn't put it down. Here was Austen writing about poor(er) people and SERVANTS! Way to surprise me, Jane.

I don't know how MP will turn out. I know it will wrap up the way they all do--everyone will be married happily, more or less. At least comfortable. I have a feeling I know who will end up with whom, but really, I don't know. She could surprise me. Ah! The charm--the suspense! of the first reading. What a lark! What a plunge!

*I still haven't read most of her juvenalia or unfinished works, like The Watsons and Sanditon, so there isn't cause for despair yet.

Sunday, June 9, 2013

Ann-Margret and Elvis star in a saucy adaptation of Mansfield Park!

This song is so apt for where I am in MP. Also, I have discovered a love for Ann-Margret I haven't felt since watching Bye Bye Birdie repeatedly as a child.

Saturday, June 8, 2013

Keep Calm and Read Jane Austen

My friend Betsy shared this with me, which was really sweet. Keep calm. Don't pick up the credit card that man tossed at you and fling it in his face. Just keep calm and then read Jane.

Just read Jane. That should be my motto for when things get stressful this summer.

Thanks for thinking of me, Betsy!

Friday, June 7, 2013

Lady B with Pug

The lovely, lazy Lady B with her pug, from the '99 movie adaptation, of which I have not seen. "The heat was enough to kill any body. It was as much as I could bear myself. Sitting and calling to Pug, and trying to keep him from the flower-beds, was almost too much for me" (59).

I love Lady Bertram: The exchange between Edmund and his mother on whether or not Fanny should go to the Grant's for dinner made me laugh; it was so delightful (170). She is completely spacey and fabulous. I am convinced she was on some kind of narcotic, because no one is that comatose.

Also, I'm a sucker for a wife with an ugly dog, like the German and her bulldog in Katherine Anne Porter's Ship of Fools. Deferred affection?

Mansfield Park: Initial Reaction

The other day I bought a new Oxford edition of Mansfield Park, which is the only novel I haven't read. It's clean and soft and full of footnotes. I am delighted with it! It's pretty shocking, actually. The characters make every one in PP seem virtuous. With the exception of Fanny and Edmund, the others are beautiful, witty, morally bankrupt flirts. There's a pun that could be about sodomy in the Navy, which almost blows my mind.* As the book goes on it is settling down a bit. Characters must fall in love and temper their callowness, I suppose.

There are two brother/sister pairs that remind me of my relationship with my sister, Jessie. Austen really holds the brother/sister relationship in high esteem: "even the conjugal tie is beneath the fraternal. Children of the same family, the same blood, with the same first associations and habits, have some means of enjoyment in their power, which no subsequent connections can supply" (183). The mischievous plotting of the Crawfords (which has begun to remind me of Dangerous Liaisons) and the pure joy of the reunited William and Fanny Price both remind me of being with my sister.

I'm interested in the POV of MP. We mostly are privy only to what Fanny sees, and for much of the book she is a very passive observer. We see only what passes her by (like the great scene in "the wilderness" at Sotherton), which gives us a critical distance from the characters, allowing us to recognize their vanity and indiscretions, which might be harder if the heroine of the novel was, say, Miss Crawford.

*The footnote in my edition explains that that is likely not what Miss Crawford is insinuating, due to Edmund's reaction. However, he is invested in seeing the best in her, and I would not be surprised if she was conscious of all meanings in her double (triple?) entendre. She's a smart, worldly cookie.

There are two brother/sister pairs that remind me of my relationship with my sister, Jessie. Austen really holds the brother/sister relationship in high esteem: "even the conjugal tie is beneath the fraternal. Children of the same family, the same blood, with the same first associations and habits, have some means of enjoyment in their power, which no subsequent connections can supply" (183). The mischievous plotting of the Crawfords (which has begun to remind me of Dangerous Liaisons) and the pure joy of the reunited William and Fanny Price both remind me of being with my sister.

I'm interested in the POV of MP. We mostly are privy only to what Fanny sees, and for much of the book she is a very passive observer. We see only what passes her by (like the great scene in "the wilderness" at Sotherton), which gives us a critical distance from the characters, allowing us to recognize their vanity and indiscretions, which might be harder if the heroine of the novel was, say, Miss Crawford.

*The footnote in my edition explains that that is likely not what Miss Crawford is insinuating, due to Edmund's reaction. However, he is invested in seeing the best in her, and I would not be surprised if she was conscious of all meanings in her double (triple?) entendre. She's a smart, worldly cookie.

Wednesday, May 29, 2013

Jane Austen to Mrs. Bennet: "No T, no shade, hunty..."

One of the most interesting moments of the Spring Gala occurred when Amy got to the q&a portion of her talk on film interpretations of P&P. A hand went up, and a woman told how glad she was to hear someone defend Mrs. Bennet, a mother who was just doing the best she could in a tight situation. Person after person voiced their surprisingly passionate agreement. Austen wasn't mocking her, they agreed; she was just presenting her realistically as a concerned mother. The vehemence of their emotion was startling: the portrayal of Mrs. B. in the 1995 version hit a nerve.

Here's the thing, though: I'm not sure Austen was so generous and sympathetic to Mrs. B., or for that matter, Mr. Collins and Mary. They are ridiculous. Mary's pedantic one-liners are jokes; Mr. Collins exemplifies all that is pompous and small-minded; and I don't think there's ever a moment we really feel genuinely for Mrs. Bennet. Do you disagree? I want to know.

I tend to agree with Woolf, who said: "sometimes it seems as if her creatures were born merely to give [her] the supreme delight of slicing their heads off" (Common Reader, 144). Austen loves them, like Elizabeth loves her mother, but she acknowledges their foolishness. Like Elizabeth, Austen laughs at what is ridiculous, but doesn't tear anyone down just for the sport of it: "I hope I never ridicule what is wise or good. Follies and nonsense, whims and inconsistencies do divert me, I own, and I laugh at them whenever I can" (P&P, 50).

I think Austen was adept at identifying the follies of people and exposing them sharply in her novels. She wasn't necessarily compassionate, but she wasn't cruel.

I didn't watch much of Drag Race, but I'm glad Jinkx Monsoon won. She was one of the few who didn't get into that "reading" culture that is briefly amusing, but quickly becomes tiresome. Most gay men I know love Mean Girls but seem to have missed the point of the movie. After years of being taunted in high school, they hope to be the popular, clever girls now, and try to do it with saucy quips that make people feel beneath them. Like Caroline Bingley, basically. Or Alyssa Edwards. And look where that got them. No Darcy, no crown. Crown? Do they win a crown in Drag Race?

Here's the thing, though: I'm not sure Austen was so generous and sympathetic to Mrs. B., or for that matter, Mr. Collins and Mary. They are ridiculous. Mary's pedantic one-liners are jokes; Mr. Collins exemplifies all that is pompous and small-minded; and I don't think there's ever a moment we really feel genuinely for Mrs. Bennet. Do you disagree? I want to know.

I tend to agree with Woolf, who said: "sometimes it seems as if her creatures were born merely to give [her] the supreme delight of slicing their heads off" (Common Reader, 144). Austen loves them, like Elizabeth loves her mother, but she acknowledges their foolishness. Like Elizabeth, Austen laughs at what is ridiculous, but doesn't tear anyone down just for the sport of it: "I hope I never ridicule what is wise or good. Follies and nonsense, whims and inconsistencies do divert me, I own, and I laugh at them whenever I can" (P&P, 50).

I think Austen was adept at identifying the follies of people and exposing them sharply in her novels. She wasn't necessarily compassionate, but she wasn't cruel.

I didn't watch much of Drag Race, but I'm glad Jinkx Monsoon won. She was one of the few who didn't get into that "reading" culture that is briefly amusing, but quickly becomes tiresome. Most gay men I know love Mean Girls but seem to have missed the point of the movie. After years of being taunted in high school, they hope to be the popular, clever girls now, and try to do it with saucy quips that make people feel beneath them. Like Caroline Bingley, basically. Or Alyssa Edwards. And look where that got them. No Darcy, no crown. Crown? Do they win a crown in Drag Race?

Wednesday, May 15, 2013

The End of P&P and the Common Reader

Yesterday I finished Pride and Prejudice. It was a terribly slow day at work, so I had plenty of time to devote to the Bennet sisters and their admirers. I spent the last pages just smiling--the ending was no less delightful the second time.

Today Christopher and I went to Winnemac Park and while he napped I wrote about P&P. I found myself trying again and again to articulate what made "good art." I know all too often that I try to force a conclusion while I'm still on the journey, and that I find comfort in labels, though they are limiting. So without making any grand statements, I want to put down a few things about Austen and why I want to spend my summer with her.

I've seen two works of art recently that for different reasons, I did not enjoy. In one I was too aware of the craft--I could see the glue and nails and it distracted me from the picture as a whole. In the other, it was all visual spectacle and nothing else. The symbolism was too opaque, and while I knew I was seeing something stunning that has inspired a cult following, I was bored. I kept wondering if I had time to get a candy bar, but since there was no narrative I had no sense of when the end would come.

P&P continued to evoke reactions from me the second time around. I still felt that punch-in-the-gut shame when Elizabeth read the letter that spoke the painful truth about her family; Mr. Collins makes me roll my eyes but his condescending letters make me angry*; and the joy of lovers reuniting still makes me grin. In other words, I was never bored. P&P makes me feel. I recognize the characters, and I recognize myself in the characters. Most shocking of all, I "just" enjoy reading it. I can appreciate the craft of the novel, but I don't need to; I can glide along with it and simply enjoy. I like that Austen can be brilliant and fun at the same time.

Virginia Woolf loved Austen for her artistry as well as for her simple appeal. Woolf wrote a collection of essays about reading for enjoyment, not for critique, and called the collection The Common Reader. Woolf's essay on Austen is insightful and lively. I love her characterizations of Austen--the baby whisked about by a fairy; the impartial guide with her staff, delineating fancy from reality; the satirist who creates characters merely to behead them; and, my personal favorite: the birdlike creature who carefully and quietly builds a little nest out of small, dusty twigs. Woolf says Austen had: "an impeccable sense of human values." Those values seem unconstrained by time.

What do you like about Austen?

*One of my favorite things on re-reading was that after Elizabeth and Jane read Collins' letter about Lydia, NOTHING WAS SAID. The story just moved on. It didn't talk about their reactions because it was obvious what was felt and Austen wasted no more time on his nauseating, pompous judgement. It was presented, and then left behind.

Today Christopher and I went to Winnemac Park and while he napped I wrote about P&P. I found myself trying again and again to articulate what made "good art." I know all too often that I try to force a conclusion while I'm still on the journey, and that I find comfort in labels, though they are limiting. So without making any grand statements, I want to put down a few things about Austen and why I want to spend my summer with her.

I've seen two works of art recently that for different reasons, I did not enjoy. In one I was too aware of the craft--I could see the glue and nails and it distracted me from the picture as a whole. In the other, it was all visual spectacle and nothing else. The symbolism was too opaque, and while I knew I was seeing something stunning that has inspired a cult following, I was bored. I kept wondering if I had time to get a candy bar, but since there was no narrative I had no sense of when the end would come.

P&P continued to evoke reactions from me the second time around. I still felt that punch-in-the-gut shame when Elizabeth read the letter that spoke the painful truth about her family; Mr. Collins makes me roll my eyes but his condescending letters make me angry*; and the joy of lovers reuniting still makes me grin. In other words, I was never bored. P&P makes me feel. I recognize the characters, and I recognize myself in the characters. Most shocking of all, I "just" enjoy reading it. I can appreciate the craft of the novel, but I don't need to; I can glide along with it and simply enjoy. I like that Austen can be brilliant and fun at the same time.

Virginia Woolf loved Austen for her artistry as well as for her simple appeal. Woolf wrote a collection of essays about reading for enjoyment, not for critique, and called the collection The Common Reader. Woolf's essay on Austen is insightful and lively. I love her characterizations of Austen--the baby whisked about by a fairy; the impartial guide with her staff, delineating fancy from reality; the satirist who creates characters merely to behead them; and, my personal favorite: the birdlike creature who carefully and quietly builds a little nest out of small, dusty twigs. Woolf says Austen had: "an impeccable sense of human values." Those values seem unconstrained by time.

What do you like about Austen?

*One of my favorite things on re-reading was that after Elizabeth and Jane read Collins' letter about Lydia, NOTHING WAS SAID. The story just moved on. It didn't talk about their reactions because it was obvious what was felt and Austen wasted no more time on his nauseating, pompous judgement. It was presented, and then left behind.

Saturday, May 11, 2013

Pride and Prejudice, 1980

I'm watching the 1980 adaptation of P&P that Amy Patterson mentioned in her Gala talk as including one of the most faithful portrayals of the Darcy character (puh-puh-puh-poker faced David Rintoul). The scene when Mrs. Bennet finds out Mr. Collins is engaged is ah-may-zing. She reminds me of Miss Piggy in A Muppets Christmas Carol.

And in searching for the date for this movie (series?), I read this post talking about a new movie called Longbourn, which tells the story from the servants' point of view. It's based on a book by Jo Baker, who says that if she had lived in Austen's time she wouldn't have been going to the ball, she'd be home sewing. Servants remain invisible in Austen's literature, as far as I know, so this must bring a new perspective. As long as it isn't just a Downstairs/Abbey sort of thing.

But back to P&P: Though some of the acting is just atrocious (Mr. Collins--seriously?) I am totally charmed by Elizabeth Garvie's portrayal of Elizabeth Bennet, and it is fun to see the story externalized. There are some things I could not have pictured, and so it's helpful to see in film. Like how dark it was at night, and how frizzy their hair was, but how lovely they still are.

And in searching for the date for this movie (series?), I read this post talking about a new movie called Longbourn, which tells the story from the servants' point of view. It's based on a book by Jo Baker, who says that if she had lived in Austen's time she wouldn't have been going to the ball, she'd be home sewing. Servants remain invisible in Austen's literature, as far as I know, so this must bring a new perspective. As long as it isn't just a Downstairs/Abbey sort of thing.

But back to P&P: Though some of the acting is just atrocious (Mr. Collins--seriously?) I am totally charmed by Elizabeth Garvie's portrayal of Elizabeth Bennet, and it is fun to see the story externalized. There are some things I could not have pictured, and so it's helpful to see in film. Like how dark it was at night, and how frizzy their hair was, but how lovely they still are.

say again?

Lydia runs off and it's like they're speaking a different language...Scotland, hackney-coach (presumptuous!), Barnet road....though I do remember learning that Scotland was the Las Vegas of Jane's time.

Friday, May 10, 2013

Stephen King Setting, Jane Austen Interaction

Yesterday, on the way to volunteering, a train on the track next to us derailed. It was rather undramatic, though I'm sure it was shocking for those in the displaced compartment. We stopped and eventually the fire department turned off the power. Moments like that (or book groups or church-led mini retreats), I flash to Stephen King novels. I love how he throws people together in chance situations. Boarding the train, we didn't really see each other, though I did notice the slight, well-dressed man with no wedding band and the young guy with a Roman nose who looked like my old housemate Jon. But then, with the lights and air conditioning off and the heat and body odor rising, we looked up, and there we were, twenty strangers stuck together in a train compartment in the middle of a day early in May. It was like the beginning to a Stephen King story.

But it was Jane who was to be the author of the hour. After the initial surprise of the derailment, I placidly returned to Elizabeth's first sighting of Pemberly, and the shock of encountering Darcy, who proceeded to charm relations, reader, and Eliza at once. And then--"May I borrow your magazine?" the well-dressed lawyer man was looking at me.

"Why, certainly," I would've said if I were Elizabeth, startled from my novel.

"Oh, sure," was what I actually said, and then, seeing him flip through the pages aimlessly, I directed him to Ariel Levy's piece on cat breeding. He was appalled at the mention of half-eaten siamese cat heads, and told me he had a chihuahua, which he would be devastated to find eaten by a thirty-pound cat.

When people started filling our car from the derailed train, he moved to sit with me, which was considerate, seeing as he was holding my New Yorker. "I saw you reading her," he gestured to P&P, "And I thought: There's someone prepared for the CTA! She's one of my favorite authors." What a delight! With Jane, you can find a friend anywhere, I think. He told me Emma was his favorite, which garnered my instant respect, as I've recently been impressed with Deresiewicz's appraisal of it. To my exclaiming on the subtlety of her masterpiece, he sort of shrugged and said: "I just liked the story." He read Northanger Abbey last summer, and when I praised its humor he responded with his pleasure in the fact that it all ended up ok.

There are as many ways to enjoy Austen as there are people you will encounter in a stalled train.

But it was Jane who was to be the author of the hour. After the initial surprise of the derailment, I placidly returned to Elizabeth's first sighting of Pemberly, and the shock of encountering Darcy, who proceeded to charm relations, reader, and Eliza at once. And then--"May I borrow your magazine?" the well-dressed lawyer man was looking at me.

"Why, certainly," I would've said if I were Elizabeth, startled from my novel.

"Oh, sure," was what I actually said, and then, seeing him flip through the pages aimlessly, I directed him to Ariel Levy's piece on cat breeding. He was appalled at the mention of half-eaten siamese cat heads, and told me he had a chihuahua, which he would be devastated to find eaten by a thirty-pound cat.

When people started filling our car from the derailed train, he moved to sit with me, which was considerate, seeing as he was holding my New Yorker. "I saw you reading her," he gestured to P&P, "And I thought: There's someone prepared for the CTA! She's one of my favorite authors." What a delight! With Jane, you can find a friend anywhere, I think. He told me Emma was his favorite, which garnered my instant respect, as I've recently been impressed with Deresiewicz's appraisal of it. To my exclaiming on the subtlety of her masterpiece, he sort of shrugged and said: "I just liked the story." He read Northanger Abbey last summer, and when I praised its humor he responded with his pleasure in the fact that it all ended up ok.

There are as many ways to enjoy Austen as there are people you will encounter in a stalled train.

Thursday, May 9, 2013

"Very little is needed to make a happy life"

...reads a fortune cookie I got after dinner with Christopher. That night is a good example of the cookie's maxim. We were off and we had enough money to enjoy a good dinner out. I was so happy to be out with Christopher I was giddy. We returned to the first restaurant where we ate when Christopher first moved to Chicago. I ordered a Pink Lady 'cause there are worse things I could do, but quickly realized I would've preferred a vodka stinger. However, that was a minor disappointment, something that only provided contrast to the fun of dinner out: overhearing conversations, watching the characters that came in; the jacket he wore and was she out with her mother dressed like that? Not to mention the food! But what I really took away from the evening was the fortune cookie that told me what I needed to hear: "Very little is needed." Just the basics, plus a good book, and someone to love, be it sister, friend, or lover. Maybe? That list is in the works.

I keep coming back to Dersiewicz's chapter on Emma and everyday matters. Up until this morning it was tangled in my mind with what a high school classmate said recently via a Facebook post: "Are people who focus on politics and their children's health and future really the same as those who indulge themselves in personal activities like reading, writing and drinking (a lot!)? Or are the former more mature and ambitious?" She clearly favored her lifestyle, or maybe felt the need to defend it. Unfortunately, she caught me up in her classic troll technique of presenting a dichotomy and as though there were only those two types of people (superior and inferior).

For a couple days I thought about what I saw as the inward vs. outward lifestyle. I've chosen the quiet life, I thought. At least for now. I decided against flight attendant training, something I'd been working towards for months. A career in customer service, the irregular schedule, and my own introverted tendencies detracted from the appeal, but also, importantly, I didn't want to give up the peaceful little life I had going.

The day I received the email inviting me again to attend training, I had finally gone to a yoga class. It felt great--so good to move my body. Afterwards, I had a vegan lunch with the cute instructor and we talked easily about books and dogs and volunteering. I left feeling invigorated, and this lunch was the impetus for me to volunteer at the cat shelter.

When I got home I took a hot bath and read Ulysses. Afterwards, propped up on a pile of pillows, surrounded by unfolded laundry, happy, and excited about my life, I checked my email and saw the invitation.

I didn't know what to do. I knew I was supposed to feel excited, but I didn't. I really was happy with life. After my surgery put off training initially, I had accepted the fact that I wasn't going to be able to go. I felt conscious of a metamorphous; that I was resting before I grew into something really beautiful and good, and I wasn't sure a life (or a few years) as a flight attendant would help me along that path. If I didn't do it, though, I'd need a really good reason to stay. Or did I? Was being happy enough?

I was concerned that if I didn't choose the more active, adventurous life, I would be "missing out;" my life would be dull, and as a consequence, I would be dull. The prospect of future regret was terrifying. And what would I do instead, really? Continue working this minimum-wage job, fading away to a nobody? While Elise and Christopher strove to meet their goals, coming home exhausted from long days of work and school, sometimes not even sleeping because there was still that paper to write...I would be there, having spent the better part of my day cleaning the kitchen and reading. How would that feel? Would life be intolerably empty? What would I have to offer anyone?

"[Austen's] genius began with the recognition that such lives as hers [which seemed uneventful compared to her aunt's or cousin's or brothers'] were very eventful indeed--that every life is eventful, if only you know how to look at it. She did not think that her existence was quiet or trivial or boring; she thought it was delightful and enthralling, and she wanted us to see that our own are, too. She understood that what fills our days should fill our hearts, and what fills our hearts should fill our novels" (Deresiewicz, 27).

And really, this isn't about an outward/inward, quiet/active life. There is no such dichotomy. Our lives--all of our lives; butcher, baker, and sex toy maker--are too rich to be crammed into some label. Let's take a note from Jane Austen and that fortune cookie, and just appreciate how good life is, how much happens every day. There's a real humility, and a kindness towards people when you believe that every life is eventful, and it's exalting.

I keep coming back to Dersiewicz's chapter on Emma and everyday matters. Up until this morning it was tangled in my mind with what a high school classmate said recently via a Facebook post: "Are people who focus on politics and their children's health and future really the same as those who indulge themselves in personal activities like reading, writing and drinking (a lot!)? Or are the former more mature and ambitious?" She clearly favored her lifestyle, or maybe felt the need to defend it. Unfortunately, she caught me up in her classic troll technique of presenting a dichotomy and as though there were only those two types of people (superior and inferior).

For a couple days I thought about what I saw as the inward vs. outward lifestyle. I've chosen the quiet life, I thought. At least for now. I decided against flight attendant training, something I'd been working towards for months. A career in customer service, the irregular schedule, and my own introverted tendencies detracted from the appeal, but also, importantly, I didn't want to give up the peaceful little life I had going.

The day I received the email inviting me again to attend training, I had finally gone to a yoga class. It felt great--so good to move my body. Afterwards, I had a vegan lunch with the cute instructor and we talked easily about books and dogs and volunteering. I left feeling invigorated, and this lunch was the impetus for me to volunteer at the cat shelter.

When I got home I took a hot bath and read Ulysses. Afterwards, propped up on a pile of pillows, surrounded by unfolded laundry, happy, and excited about my life, I checked my email and saw the invitation.

I didn't know what to do. I knew I was supposed to feel excited, but I didn't. I really was happy with life. After my surgery put off training initially, I had accepted the fact that I wasn't going to be able to go. I felt conscious of a metamorphous; that I was resting before I grew into something really beautiful and good, and I wasn't sure a life (or a few years) as a flight attendant would help me along that path. If I didn't do it, though, I'd need a really good reason to stay. Or did I? Was being happy enough?

I was concerned that if I didn't choose the more active, adventurous life, I would be "missing out;" my life would be dull, and as a consequence, I would be dull. The prospect of future regret was terrifying. And what would I do instead, really? Continue working this minimum-wage job, fading away to a nobody? While Elise and Christopher strove to meet their goals, coming home exhausted from long days of work and school, sometimes not even sleeping because there was still that paper to write...I would be there, having spent the better part of my day cleaning the kitchen and reading. How would that feel? Would life be intolerably empty? What would I have to offer anyone?

"[Austen's] genius began with the recognition that such lives as hers [which seemed uneventful compared to her aunt's or cousin's or brothers'] were very eventful indeed--that every life is eventful, if only you know how to look at it. She did not think that her existence was quiet or trivial or boring; she thought it was delightful and enthralling, and she wanted us to see that our own are, too. She understood that what fills our days should fill our hearts, and what fills our hearts should fill our novels" (Deresiewicz, 27).

And really, this isn't about an outward/inward, quiet/active life. There is no such dichotomy. Our lives--all of our lives; butcher, baker, and sex toy maker--are too rich to be crammed into some label. Let's take a note from Jane Austen and that fortune cookie, and just appreciate how good life is, how much happens every day. There's a real humility, and a kindness towards people when you believe that every life is eventful, and it's exalting.

Monday, May 6, 2013

A Jane Austen Education: Emma

Everything about A Jane Austen Education looks like it's geared towards women, from its typeface and effusive subtitle ("How Six Novels Taught Me About Love, Friendship, and the Things That Really Matter") to its paper doll illustration on the soft lavender background. I was scanning it at the bookstore yesterday and it surprised me, on page two, to realize the author was a man (William Deresiewicz). Ok, well that was cool. I don't often hear about Jane Austen from men, so I was interested. And then surprised again on page to find this was a straight man. Sold!

His books is divided into seven chapters, six of which deal with a novel and a life lesson he learned while reading. The first chapter is on Emma, a novel that I trudged through a couple years ago, all the while preferring the Clueless version. Deresiewicz is much smarter than I am, because he fell in love with Austen while reading it, and informed me it is considered to be her masterpiece. Challenge accepted! I will try again.

Deresiewicz alternates between portraying his 26-year-old self as a raging sexist; totally arrogant and unlikeable, and observations on Emma and Austen that are touchingly passionate. I have a suspicion he's going overboard on how unlikable he was, as that is the current vogue in memoirs (Giles Harvey on the "Failure Memoir"), and he was obviously really intelligent. How else could he come to the conclusion while reading Emma that Austen incited a certain response in her readers, in order to expose them and show us our own "ugly face" (12)? And by the way, that observation blew my mind.

Deresiewicz does offer the opinion of Austen I tried to articulate yesterday. To his modernist-loving younger self, Austen was the godmother of those boring 19th century British novels: "What could be duller [...] than a bunch of long, heavy novels, by women novelists, in stilted language, on trivial subjects?" (2) and he quotes Mark Twain on Austen, who said her work made him feel "'like a barkeep entering the kingdom of heaven.' 'It seems a great pity to me,' he taunted an Austen fan, 'that they allowed her to die a natural death.' 'Every time I read Pride and Prejudice,' he told another friend, 'I want to dig her up and hit her over the skull with her own shinbone'" (19).

And yet, this "'little old maid'" (19) would teach Deresiewicz, in his words: "everything I know about everything that matters" (1).

Well, ok.

It was exciting to read the first chapter, just because it's wonderful to read someone articulate why you love something. Like my former classmate, Maggie, said about P&P and E: "There's something comforting about them. Life gets real, but not in a overly horrific way" or the character Humberstall in Rudyard Kipling's "The Janeites:" "There's no one to touch Jane when you're in a tight place" (20). Yes, her writing is comforting. It's not big and dramatic, you aren't going to be dragged through the wringer, and they all have happy endings.

So what? When I put it that way, it does sound dull. But her novels absolutely are not. They are lively and fun, she is totally refreshing and on point, as when she describes dancing with an unappealing partner: "Mr. Collins, awkward and solemn, apologizing instead of attending, and often moving wrong without being aware of it, gave her all the shame and misery which a disagreeable partner for a couple of dances can give. The moment of her release from him was ecstasy (78-79, P&P). How charming is that? I could listen to that voice for hours, couldn't you?

His books is divided into seven chapters, six of which deal with a novel and a life lesson he learned while reading. The first chapter is on Emma, a novel that I trudged through a couple years ago, all the while preferring the Clueless version. Deresiewicz is much smarter than I am, because he fell in love with Austen while reading it, and informed me it is considered to be her masterpiece. Challenge accepted! I will try again.

Deresiewicz alternates between portraying his 26-year-old self as a raging sexist; totally arrogant and unlikeable, and observations on Emma and Austen that are touchingly passionate. I have a suspicion he's going overboard on how unlikable he was, as that is the current vogue in memoirs (Giles Harvey on the "Failure Memoir"), and he was obviously really intelligent. How else could he come to the conclusion while reading Emma that Austen incited a certain response in her readers, in order to expose them and show us our own "ugly face" (12)? And by the way, that observation blew my mind.

Deresiewicz does offer the opinion of Austen I tried to articulate yesterday. To his modernist-loving younger self, Austen was the godmother of those boring 19th century British novels: "What could be duller [...] than a bunch of long, heavy novels, by women novelists, in stilted language, on trivial subjects?" (2) and he quotes Mark Twain on Austen, who said her work made him feel "'like a barkeep entering the kingdom of heaven.' 'It seems a great pity to me,' he taunted an Austen fan, 'that they allowed her to die a natural death.' 'Every time I read Pride and Prejudice,' he told another friend, 'I want to dig her up and hit her over the skull with her own shinbone'" (19).

And yet, this "'little old maid'" (19) would teach Deresiewicz, in his words: "everything I know about everything that matters" (1).

Well, ok.